Cobalt Strike DFIR: Listening to the Pipes

Happy Holidays! This weeks update is a bit of a shorter blog, mostly to keep me busy while on Christmas holidays!

Recently I stumbled across svch0st’s “Guide to Named Pipes and Hunting for Cobalt Strike Pipes”. If you haven’t read it, I highly recommend it.

Named Pipes have been something that I’ve thought about for a while, especially how do we take advantage of them during active compromise. Named Pipes have worked their way into a lot of common malicious behaviour, especially with:

Modulated Implants: Communicating between malicious children processes back to the implant core, often utilized with Key Loggers.

Privilege Escalation: The Potato family being the most frequent recently, but even Metasploit’s “Get-System” uses Named Pipes.

Lateral Movement: Many system pipes allow for remote code execution.

Persistence: Some implants (such as Cobalt Strike) can now listen on a Named Pipe, providing a static backdoor: no beacons, no ports, just a named pipe!

Often it can be advantageous to leave an actor on a network, while you fully scope out the extent of the compromise and their accesses. This can ensure that you fully remove the actor in one sweep, rather than playing whack a mole for the next few months.

If you are monitoring an actor though, you need to make sure you have full coverage over their actions. But the problem is, how do we monitor these pipes? I searched across a few options, but none of them seemed quite right:

ETW: No great providers for monitoring all named pipes, all though you can capture SMB traffic which will show remote Named Pipe exploitation.

Kernel: Seemed overkill, especially when monitoring implants. The unknown could be a high risk of blue screens.

Eventually I came to the idea of API hooking, what if we used actor techniques against them and hooked common Named Pipe functions. If we hook these functions, that puts us in a unique spot to log, respond and react to actor activities. So, what are the common Named Pipe functions?

How Named Pipes Work

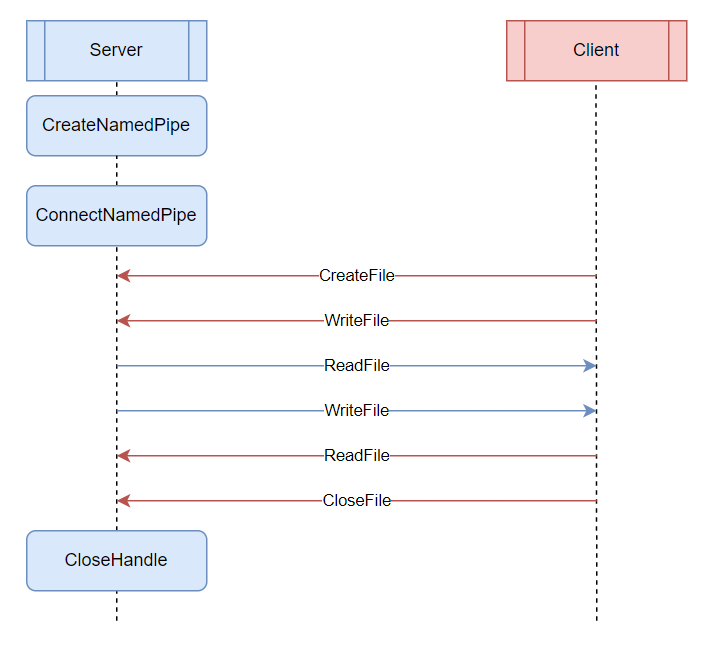

Named Pipes work in a client / server model.

The server is responsible for setting up the Named Pipe, then waits for one or many clients to connect. The Server and Clients then treat the Named Pipe as a file, using CreateFile, ReadFile and Write file to communicate through the pipe. Once done, they can both close the pipe like a standard file.

To understand how modulated malware uses Named Pipes, you just need to replace “server” with the core implant, and “client” as the module, such as a key logger.

Because Named Pipes normally go by unnoticed, most malware (that I’ve observed) don’t bother encrypting data being sent over a Named Pipe. Because of that, we’re left in a prime opportunity to get a copy of the data being sent.

Note: There are a few other functions that are sometimes used with Named Pipes, so you’d probably want to check how your target uses Named Pipes before hooking them. Some other functions include WaitNamedPipe, CallNamedPipe and TransactNamedPipe.

API Hooking Workflow

I wrote an injectable DLL, that once attached to a process will iterate through each of the standard Named Pipe functions and install a hook. The functions I was hooking in my PoC are:

CreateFileA

CreateFileW

ReadFile

WriteFile

CreateNamedPipe

Note: I used EasyHook for this proof of concept, so I wasn’t reinventing the wheel with API hooking and reliability. If this were to be productionized, I would not recommend using EasyHook, as you’re required to load the EasyHook{32/64}.dll which will make your presence extremely obvious.

For the standard file interaction functions, such as Create, Read and Write, I implement a quick check to see if the function is targeting a Named Pipe. If not, return it right away, so we’re not holding up the process.

if (wcsstr(lpFileName, L"\\\\.\\pipe\\") == NULL) goto Cleanup;

Once we know we’ve hooked a Named Pipe, we capture the relevant data before allowing the process to continue as normal.

But how do we get our data back to us?

Initially I had two solutions but they both had big flaws:

Use Easy Hooks IPC communications: Sounds great in theory, but in production we wouldn’t want to send out an individual controller.

Use ETW: Sound great in theory, but that would depend on the injected process have the rights to create a provider and send events. This would also have a whole bunch of overhead, installing the ETW manifest.

So the solution that I landed on, funnily enough, was named pipes!

I capture the data from the hooked parameters and place them within a struct (this includes copying the buffer into a char array). I used a separate struct for each hooked function to ensure that relevant data was captured. That initial byte of each structure references an enum. This can help us separate the different hook types, so we can differentiate them on the server end.

The structure is then written to the named pipe as a char array. Once the data is received by the name pipe server, I can read the first byte to decode the byte array into the hook structure.

enum HOOKS { CreateA = 0x00, CreateW = 0x01, Read = 0x02, Write = 0x03, CreateP = 0x04 };

Note: EasyHook allows us to exclude our thread from being captured by our hooked function. This allows us to use the Named Pipe functions without capturing ourselves in an infinite loop. I also added a check to ignore any functions targeting the Named Pipe “\\.\pipe\PipeHook”.

Production Ready Code?

Proof of Concepts are great but to actually use this in the wild, we need to consider:

How we inject the DLL,

How we read the traffic,

How we do this at scale.

Similar to previous posts, Velociraptor is an open source EDR that allows us to remotely monitor and interact with our hosts. The problem is, there’s no real functionality to either inject a DLL or setup a Named Pipe. To fix this, I just wrote some plugins to enable this capability!

While Velociraptor is written in GoLang, it is very easy to call straight C functions. Because of this, I used the standard DLL injection technique: Loading a Library, then creating a remote thread executing it. There’s nothing to special about it, I just wanted to get a PoC working.

Note: If you were going to do this within a live environment, you should probably look to use a reflective injection technique to hide your DLL from basic actor triaging.

A similar process was followed for the Named Pipe Server, I created the plugin “watch_pipe”. I kept it simple with only a single argument, pipe name. I figured this could be a useful plugin for other projects, where I want to get data back to Velociraptor without writing to disk.

type _WatchPipePluginArgs struct { PipeName string `vfilter:"required,field=pipe_name,doc=The name of the named pipe."` }

For the Named Pipe aspect of the code, I used the npipe package for Go-Lang. Again, laziness on my part. But this provided a super quick solution and saved me the time of manually importing the Windows API functions. Soo…. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

The code itself is pretty simple, I have a routine that creates the Named Pipe then just loops through waiting for a connection. Once I receive a message, I transform the it into a byte array so I can decode them into their structures in post analysis. Velociraptor expects data to be sent within a dictionary, so I just through it in with the “data” row.

// Create the pipe. conn, err := npipe.Listen(fmt.Sprintf(`\\.\pipe\%s`, pipename)) if err != nil { scope.Log("create_pipe: %v", err) return } scope.Log("Created Named Pipe: %s", fmt.Sprintf(`\\.\pipe\%s`, pipename)) for { // Check for message. msg, err := conn.Accept() if err != nil { scope.Log("conn_accept: %v", err) continue } // Read the message into a buffer. buf := make([]byte, 256) size, err := msg.Read(buf) if err != nil || size <= 0 { scope.Log("msg_read: %v", err) continue } // Convert the message into a dictionary. event := ordereddict.NewDict(). Set("Data", fmt.Sprintf("%x", buf)) scope.Log("msg: %v", event) // Output to our channel. select { case <-ctx.Done(): return case output_chan <- event: } }

Once the data is received, it comes through with just three fields: Time, Data and Client ID. You can see the first byte in the image below refers to the enum that we referenced above. Each of those messages being a “WriteFile” hook.

Wrap up

While this code is nowhere near production ready, it was nice to see that API hooking could be a feasible way to track malicious Named Pipe usage and could warrant further investigation.

A point worth mentioning is that I didn’t have a copy of Cobalt Strike readily available, so I quickly wrote up my own Named Pipe server and client. Ideally I would like to test this with Cobalt Strike in the future. This could also be tested with other malware families.

This also provided a nice basis for a “watch_pipe” plugin for Velociraptor, a more lightweight and lower privileged method for getting tool events back to your Velociraptor server.

I’ve got the Named Pipe plugin on my forked Velociraptor repo on GitHub if you want to try it out yourself. Check the “watch_pipe” branch!

As always, any questions, feel free to reach out to me on Twitter! Otherwise, Happy Holidays!